Reprinted with permission of the News-Register. Find more News-Register stories about Linfield College here.

By Nicholas Buccola

March 7, 2014

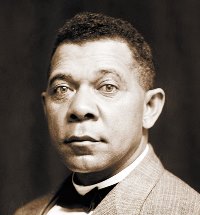

Booker T. Washington, above, wrote “Up from Slavery” and believed that industrial education was the key to African-American progress.

A centuries-old American debate about higher education continues to occupy the minds of lawmakers, cultural critics and the parents of high school students: Should young people enroll in vocational training at trade schools or community colleges, or seek broad training in the liberal arts at a college or university?

Two great African-American thinkers, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, sought to answer this question. Washington’s “Up from Slavery,” and Du Bois’ “The Souls of Black Folk” are essential reading for all Americans and, in the wake of February, America’s annual Black History Month, we would do well to reflect on the messages of both texts.

Washington was born into slavery in 1856. In “Up from Slavery,” he describes his ascent from an impoverished childhood to national prominence after assuming leadership of the Tuskegee Institute in 1881. As one of the country’s most significant African-American leaders, he interacted with elites such as Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller and President Theodore Roosevelt.

Washington is most famous for his advocacy of “industrial education” and his belief that economic advancement — not political agitation — was key for African-American progress.

Du Bois, born in Massachusetts in 1868, became one of the most prominent intellectuals and activists of his day. In “The Souls of Black Folk,” Du Bois offered profound reflections on race in America, and he took Washington to task for what he argued was a fundamentally flawed “conception of education.”

Washington criticized “New England education” as “mere book education,” as an impractical form of education that failed to teach students “the dignity of labor.” He said “one of the saddest things” he ever witnessed was an educated young man “with grease on his clothing, filth all around him, and weeds in the yard and garden, engaged in studying a French grammar.”

In Washington’s mind, the educational system did not prepare this young man to provide the world with what it needed. He wrote that most communities have a greater need for students trained in the “best methods of laundrying” than in the “analysis of Greek sentences.”

Du Bois issued a sharp critique of Washington’s program of industrial education. Why, he asked, shouldn’t African-Americans seek “an education that encourages aspiration, that sets the loftiest ideals and seeks a result of culture and character rather than breadwinning”?

The “ideal of book-learning,” wrote Du Bois, is to encourage students to engage in “reflection and self examination” with the hope of becoming better equipped to achieve “self-realization” and “self-respect.” He argued that Washington’s educational program was rooted in a shallow, materialistic understanding of human nature and human excellence.

Du Bois defended exactly the sort of “book-learning” Washington criticized. The “true college,” Du Bois declared, “will ever have one goal — not to earn meat, but to know the end and aim of that life which meat nourishes.”

The debate between Washington and Du Bois lives on in arguments about the proper role of higher education in our society. Yet, despite the sharp contrast drawn here, Washington and Du Bois actually believed we need not — indeed we should not — choose one path or the other; we must choose both.

While Washington is best remembered for his emphasis on “industrial and technical education,” he said such training should be offered “in addition to” training “that gives strength and culture to the mind.” Washington was not opposed to book education, but rather to merely book education. A proper college curriculum, he concluded, should consist of “a generous education of the hand, head, and heart.” In the parlance of our time, his vision included the liberal arts and a strong dose of experiential learning.

For his part, Du Bois acknowledged “a rule of inequality” holding that some individuals “are fitted to know and some to dig; that some (have) the talent and capacity of university men, and some the talent and capacity of blacksmiths …” This rule of inequality may be regrettable, but Du Bois contended it is a fact of life.

Du Bois was deeply offended by operation of the rule of inequality according to standards other than merit. To whites seeking to exclude African-Americans from the halls of the best universities, and to figures like Washington who seemed far too willing to “cease striving” to be admitted in those halls, Du Bois demanded that every student — regardless of race — be treated according to his ability.

“Teach the workers to work and the thinkers to think,” Du Bois argued. “To seek to make the blacksmith a scholar is almost as silly as the modern scheme of making the scholar a blacksmith; almost, but not quite.”

As we grapple with how to strike the balance between liberal and vocational instruction in higher education, we would do well to remember this great debate between Washington and Du Bois.

There is little doubt that the “experiential learning” Washington offered his students better prepared them to be useful, but Du Bois reminds us that something more is needed to help students flourish. Perhaps the most important task of higher education is to provide students with invitations to reflect on what it means to be human and to deliberate on just what sorts of humans they aspire to be.

As one of my colleagues often says, sometimes the experience our students most need is to sit down and read a great book.

Guest writer Nicholas Buccola is associate professor of political science and the founding director of the Frederick Douglass Forum on Law, Rights, and Justice at Linfield College. He is the author of “The Political Thought of Frederick Douglass,” a paperback published by New York University Press.